Ποδόσφαιρο και Αυτοδιαχείριση

Yavor Tarinski

Μετάφραση: Ιωάννα Μαραβελίδη

Το ποδόσφαιρο άνθισε στις φτωχογειτονιές. Δεν απαιτούσε χρήματα και για να παιχτεί δεν χρειαζόταν τίποτα άλλο παρά καθαρή επιθυμία.

Εδουάρδο Γκαλεάνο

Στο βιβλίο του «Τα χίλια πρόσωπα του ποδοσφαίρου» (1995) ο Εδουάρδο Γκαλεάνο αναφέρεται στην εμπορευματοποίηση του πιο δημοφιλούς αθλήματος του πλανήτη και στην αποκόλλησή του απ’τις ρίζες του. Μέσα σε αυτό, επισημαίνει πως «απ’τη στιγμή που το άθλημα έγινε βιομηχανία, η ομορφιά που άνθιζε από τη χαρά του παιχνιδιού καταστράφηκε ολοκληρωτικά. Το επαγγελματικό ποδόσφαιρο καταδικάζει όλα όσα θεωρεί άχρηστα, και το “άχρηστα” σημαίνει μη κερδοφόρα». Για μία ακόμα φορά είδαμε ακριβώς αυτό, στο τελευταίο Παγκόσμιο Κύπελλο στη Βραζιλία όπου το μοντέρνο ποδόσφαιρο εμφανίστηκε ως αυτό που πράγματι είναι: ένας μηχανισμός που εξυπηρετεί τη λογική της συνεχούς συσσώρευσης κεφαλαίου, επιθετικός ως προς τους «από τα κάτω», οι οποίοι δεν έχουν την πολυτέλεια να συμμετέχουν και να επηρεάσουν αυτό το πανηγύρι της καταναλωτικής κουλτούρας, παρά μόνο ως παθητικοί καταναλωτές.

Σε αντίθεση με πολλούς αριστερούς διανοούμενους, που ισχυρίζονται πως «το ποδόσφαιρο ευνουχίζει τις μάζες και εκτροχιάζει τον επαναστατικό τους ζήλο»(Galeano, 1995), ο Γκαλεάνο αναφέρει πως το ποδόσφαιρο είναι βαθιά ριζωμένο στα σπλάχνα των κοινών ανθρώπων και μέσω αυτού μας δίνεται η δυνατότητα να λάμψει η ανθρώπινη φαντασία, η οποία σήμερα αμβλύνεται απ’την γραφειοκρατική λογική. Όπως λέει: «για πολλά χρόνια το ποδόσφαιρο παιζόταν με διαφορετικούς τρόπους, μοναδικές εκφράσεις της προσωπικότητας του κάθε ανθρώπου και η διατήρηση αυτής της ποικιλομορφίας μου φαίνεται σήμερα πιο απαραίτητη από ποτέ». Σύμφωνα με τον Αντόνιο Νέγκρι, «το μεγάλο πλεονέκτημα του ποδοσφαίρου έγκειται στην ικανότητά του, να κάνει τους ανθρώπους να συνομιλούν μεταξύ τους» [1], σε μία εποχή όπου η αποξένωση αλλοιώνει τον κοινωνικό ιστό.

Σκεπτόμενοι τα παραπάνω, το ποδόσφαιρο μπορεί να ειδωθεί ως κοινό αγαθό, το οποίο μοιράζεται σε όλους όσους το αγαπούν και το εξασκούνε, αν και πάνω σε αυτό έχει γίνει λυσσαλέα προσπάθεια ιδιωτικοποίησης. Παρόλο που εκατομμύρια άνθρωποι σε όλο τον κόσμο μοιράζονται το ίδιο πάθος για το άθλημα, δεν επηρεάζουν καθόλου τις αποφάσεις των αγαπημένων τους ομάδων. Αυτές βρίσκονται στα χέρια των διεφθαρμένων ποδοσφαιρικών ομοσπονδιών και οργανισμών, που έχουν ως προτεραιότητα τη μεγιστοποίηση των κερδών, κάτι το οποίο φυσικά παράγει διαρκώς σκάνδαλα διεθνούς κλίμακας (όπως το πρόσφατο σκάνδαλο με εμπλεκόμενο τον πρόεδρο της FIFA, Σεπ Μπλάτερ).

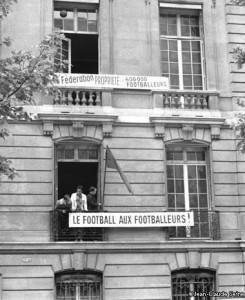

Όμως, 27 χρόνια πριν από αυτές τις λέξεις του Γκαλεάνο, κατά τη διάρκεια του Μάη του ΄68 στο Παρίσι, πραγματοποιήθηκε ένας απ΄τους πρώτους αγώνες ενάντια στη γραφειοκρατικοποίηση και την ιδιωτικοποίηση του ποδοσφαίρου. Συγκεκριμένα, ενώ εκατομμύρια εργαζομένων βρίσκονταν σε απεργία, μαθητές έκαναν καταλήψεις στα πανεπιστήμια, ο πρόεδρος έφευγε από τη χώρα και η Γαλλία φαινόταν στα πρόθυρα μιας επανάστασης, τότε μια πρωτοβουλία ποδοσφαιριστών κατέλαβε τα κεντρικά γραφεία της Γαλλικής Ομοσπονδίας Ποδοσφαίρου για έξι μέρες [2]. Στην ανακοίνωσή τους τονίζουν ότι το ποδόσφαιρο έχει αρπαχτεί από τα χέρια των παικτών και των φιλάθλων και έχει υποταχθεί στην υπηρεσία του κέρδους. Ένα απ΄τα κύρια αιτήματά τους ήταν η άμεση απομάκρυνση των κερδοσκόπων του ποδοσφαίρου, μέσω δημοψηφίσματος όλων των 600.000 ποδοσφαιριστών και ο εκδημοκρατισμός του αθλήματος.

Όμως, 27 χρόνια πριν από αυτές τις λέξεις του Γκαλεάνο, κατά τη διάρκεια του Μάη του ΄68 στο Παρίσι, πραγματοποιήθηκε ένας απ΄τους πρώτους αγώνες ενάντια στη γραφειοκρατικοποίηση και την ιδιωτικοποίηση του ποδοσφαίρου. Συγκεκριμένα, ενώ εκατομμύρια εργαζομένων βρίσκονταν σε απεργία, μαθητές έκαναν καταλήψεις στα πανεπιστήμια, ο πρόεδρος έφευγε από τη χώρα και η Γαλλία φαινόταν στα πρόθυρα μιας επανάστασης, τότε μια πρωτοβουλία ποδοσφαιριστών κατέλαβε τα κεντρικά γραφεία της Γαλλικής Ομοσπονδίας Ποδοσφαίρου για έξι μέρες [2]. Στην ανακοίνωσή τους τονίζουν ότι το ποδόσφαιρο έχει αρπαχτεί από τα χέρια των παικτών και των φιλάθλων και έχει υποταχθεί στην υπηρεσία του κέρδους. Ένα απ΄τα κύρια αιτήματά τους ήταν η άμεση απομάκρυνση των κερδοσκόπων του ποδοσφαίρου, μέσω δημοψηφίσματος όλων των 600.000 ποδοσφαιριστών και ο εκδημοκρατισμός του αθλήματος.

Αργότερα, στα τέλη της δεκαετίας του ’70 οι ποδοσφαιριστές της βραζιλιάνικης ομάδας Κορίνθιανς, αποφάσισαν να πάρουν στα χέρια τους την ομάδα στην οποία έπαιζαν. Εμπνευσμένοι από τον τότε αρχηγό της ομάδας, Σώκρατες [3], οι παίκτες άρχισαν να συζητούν και να ψηφίζουν με μία απλή ανάταση των χεριών για όλα τα ζητήματα που τους επηρέαζαν, από απλά πράγματα όπως τι ώρα θα φάνε το μεσημεριανό τους μέχρι το να μην συμμορφώνονται στο μισητό concentração, μία συνήθης πρακτική στη Βραζιλία όπου οι παίκτες παρέμεναν στην ουσία κλειδωμένοι στο ξενοδοχείο για μία ή και δύο ημέρες πριν τον αγώνα. Μία απ΄τις πιο αξιοσημείωτες αποφάσεις που πήραν ήταν το 1982, όταν στην, υπό στρατιωτική δικτατορία από το 1964, Βραζιλία οι παίκτες της Κορίνθιανς έβγαιναν στον αγωνιστικό χώρο για ένα ακόμα παιχνίδι έχοντας γραμμένο στις φανέλες τους το σύνθημα «Ψηφίστε στις 15», προτρέποντας τον κόσμο να συμμετάσχει στις πρώτες πολυκομματικές εκλογές. Αυτό το μοντέλο αυτοδιεύθυνσης που δημιούργησαν, έμεινε στην ιστορία ως Κορινθιακή Δημοκρατία (Democracia Corinthiana) [4]. Παρ’όλα αυτά, σε αυτό το πείραμα αν και οι παίκτες είχαν λόγο σε όσα τους επηρέαζαν, οι φίλαθλοι, δεν εμπλέκονταν καθόλου στην δημοκρατική διαδικασία.

Ένα παράδειγμα, όπου η διαχείριση ενός αθλητικού συλλόγου υπήρξε πραγματικά στα χέρια των φιλάθλων, είναι η περίπτωση της Έμπσφλιτ Γιουνάιτεντ (Ebbsfleet United), η οποία αγωνίζεται μεταξύ 5ης και 6ης κατηγορίας του αγγλικού ποδοσφαίρου.  Στις 13 Νοεμβρίου 2007, ανακοινώθηκε ότι η ιστοσελίδα “MyFootballClub” (MyFC), έκανε πρόταση να αγοράσει το σύλλογο. Περίπου 27.000 μέλη του MyFC μάζεψαν τις απαραίτητες £700.000 (35 λίρες ο καθένας) με σκοπό την εξίσου συμμετοχή στην αγορά και διοίκηση της ομάδας. Όλα τα μέλη κατείχαν μόνο από μία μετοχή ώστε να υπάρχει ίση συμμετοχή στις αποφάσεις, χωρίς να λαμβάνουν μέρισμα ή κάποιο άλλο οικονομικό όφελος. Όλοι είχαν δικαίωμα ψήφου για τα θέματα της ομάδας, όπως για τις μεταγραφές, τον προϋπολογισμό, την τιμή των εισιτηρίων ακόμα και για την επιλογή της ενδεκάδας που αγωνίζεται κάθε φορά και όλα αυτά μέσω ψηφοφορίας στο διαδίκτυο. Ο προπονητής Λάιαμ Ντέις, όπως και οι βοηθοί του, αρκέστηκαν πλέον στο ρόλο των γυμναστών-εκπαιδευτών χωρίς περαιτέρω αρμοδιότητες. Με αυτό το πλαίσιο αμεσοδημοκρατικής διαχείρισης από τους ίδιους τους φιλάθλους, η Έμπσφλιτ Γιουνάιτεντ κατάφερε να κερδίσει το FA Trophy, το 2008, γίνοντας έτσι η πρώτη ομάδα από το Κεντ που κατακτά αυτόν τον τίτλο, καθώς και το τοπικό Κύπελλο του Κέντ.

Στις 13 Νοεμβρίου 2007, ανακοινώθηκε ότι η ιστοσελίδα “MyFootballClub” (MyFC), έκανε πρόταση να αγοράσει το σύλλογο. Περίπου 27.000 μέλη του MyFC μάζεψαν τις απαραίτητες £700.000 (35 λίρες ο καθένας) με σκοπό την εξίσου συμμετοχή στην αγορά και διοίκηση της ομάδας. Όλα τα μέλη κατείχαν μόνο από μία μετοχή ώστε να υπάρχει ίση συμμετοχή στις αποφάσεις, χωρίς να λαμβάνουν μέρισμα ή κάποιο άλλο οικονομικό όφελος. Όλοι είχαν δικαίωμα ψήφου για τα θέματα της ομάδας, όπως για τις μεταγραφές, τον προϋπολογισμό, την τιμή των εισιτηρίων ακόμα και για την επιλογή της ενδεκάδας που αγωνίζεται κάθε φορά και όλα αυτά μέσω ψηφοφορίας στο διαδίκτυο. Ο προπονητής Λάιαμ Ντέις, όπως και οι βοηθοί του, αρκέστηκαν πλέον στο ρόλο των γυμναστών-εκπαιδευτών χωρίς περαιτέρω αρμοδιότητες. Με αυτό το πλαίσιο αμεσοδημοκρατικής διαχείρισης από τους ίδιους τους φιλάθλους, η Έμπσφλιτ Γιουνάιτεντ κατάφερε να κερδίσει το FA Trophy, το 2008, γίνοντας έτσι η πρώτη ομάδα από το Κεντ που κατακτά αυτόν τον τίτλο, καθώς και το τοπικό Κύπελλο του Κέντ.

Το 2013, μετά από μία σοβαρότατη πτώση των μελών (από 32.000 που ήταν στο αποκορύφωμά τους, έπεσαν στους 1.000), τα εναπομείναντα μέλη ψήφισαν υπέρ του να πουλήσουν πλέον τις μετοχές που είχαν στην ομάδα. Αυτή η πτώση του ενδιαφέροντος μπορεί να αποδοθεί σε πολλούς παράγοντες: στο διαρκή σκεπτικισμό που εκφραζόταν απ’τους επισήμους του συλλόγου, οι οποίοι κατηγορούσαν την ιστοσελίδα MyFC ότι καταστρέφει τον σύλλογο(!) [5], στο γεγονός ότι κατά τη διάρκεια της τωρινής παγκόσμιας κρίσης ο σύλλογος άρχισε να γίνεται οινονομικό βάρος για κάποια από τα μέλη του, ή στο γεγονός ότι τα ίδια τα μέλη είδαν την ενασχόλησή τους αυτή ως χόμπυ και δεν συνέδεσαν αυτήν την δημοκρατική τους εμπειρία με ένα ευρύτερο πρόταγμα άμεσης δημοκρατίας, που θα κάλυπτε όλες τις σφαίρες της κοινωνικής ζωής.

Στις παραπάνω περιπτώσεις, φυσικά και μπορούμε να βρούμε ατέλειες: στην περίπτωση της Κορίνθιανς, παρόλο που ο ρόλος των παικτών επεκτάθηκε πέρα από το τερέν, πολιτικοποιήθηκε και διανθίστηκε με αμεσοδημοκρατικά χαρακτηριστικά, οι φίλαθλοι όμως παρέμειναν έξω από αυτήν τη διαδικασία. Στη δεύτερη περίπτωση της Έμπσφλιτ Γιουνάιτεντ, βλέπουμε ακριβώς το ίδιο πρόβλημα αλλά απ΄την αντίθετη πλευρά. Ωστόσο, αποτελούν μία σημαντική εμπερία και παρακαταθήκη μοντέλων αυτοδιαχείρισης, που αν συνδυαστούν μπορούν να μας δώσουν τη βάση για την απεμπλοκή του ποδοσφαίρου από το δίπολο κρατικό-ιδιωτικό και τη θέασή του ως κοινού αγαθού. Για να διαρκέσει ένα τέτοιο εγχείρημα, χρειάζεται, όπως προείπαμε, η σύνδεσή του με ένα ευρύτερο πρόταγμα κοινωνικού εκδημοκρατισμού. Όπως τονίζει και ο Καστοριάδης, η άμεση δημοκρατία δεν μπορεί να υπάρξει μόνο σε μία κοινωνική σφαίρα, γιατί τότε οι ανισότητες που υπάρχουν στις υπόλοιπες σφαίρες, και προέρχονται ακριβώς από τον μη δημοκρατικό τους χαρακτήρα, αργά ή γρήγορα, θα επηρεάσουν και την ίδια [6].

Η εξέλιξη του ποδοσφαίρου σε κοινό αγαθό, διαχειριζόμενο απ΄τους παίκτες και τους φιλάθλους είναι μία εφικτή προοπτική και υπάρχουν πλέον οι προσπάθειες γι’αυτό. Όπως αναφέρει και ο Γκαλεάνο «το ποδόσφαιρο είναι πολλά παραπάνω από μία μεγάλη εταιρεία διοικούμενη από κάποιους φεουδάρχες απ’την Ελβετία. Το δημοφιλέστερο άθλημα στον πλανήτη επιθυμεί να προσφέρει τις υπηρεσίες του στον κόσμο που το αγκαλιάζει».

Σημειώσεις:

[1] libcom.org/library/negri-football-class-struggle

[2] libcom.org/library/football-footballers

[3] libcom.org/library/s-crates-midfielder-anti-dictatorship-resister

[4] en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corinthians_Democracy

[5] news.bbc.co.uk/local/london/hi/front_page/newsid_8967000/8967067.stm

[6] athene.antenna.nl/ARCHIEF/NR01-Athene/02-Probl.-e.html